• “A witty, readable work easily digestible by most well-read Catholics.”

• “A witty, readable work easily digestible by most well-read Catholics.”

• “Shows how the historical evidence for many of the changes to pre-Tridentine times was merely a ruse developed by the modernist reformers.”

• “I highly recommend this book — even reading it multiple times as I myself did.”

• “Father Cekada’s exhaustive theological critique demands a response from the ‘reform of the reform’ crowd.”

REVIEWER: Brian Mershon is a commentator on cultural issues from a classical Catholic perspective, and holds a Master’s degree in theology. His trade is in media relations, and his vocation is as a husband to his beloved wife Tracey and father to his seven living children. He attempts to assist his family and himself in attaining eternal salvation through frequent attendance at the Traditional Latin rite of Mass, homeschooling, and building Catholic culture in the buckle of the Bible Belt of Greenville, South Carolina. His writings have appeared in numerous media outlets, including Inside the Vatican, The Remnant, Homiletic and Pastoral Review, The Wanderer and Christian Order.

WEBSITE: Renew America began in 2002 as a grassroots support for conservative political commentator and presidential candidate Allen Keyes, and since then has amassed a large following among conservatives in the United States.

BRIAN MERSHON’S REVIEW: Many of you may be familiar with Father Anthony Cekada’s short booklet entitled Problems with the Prayers of the Modern Mass, originally published by TAN Books. As Catholics are about to become inundated with news stories and catechesis from the pews on the new translation of the Novus Ordo Missae in English, which goes live this Advent, every Catholic would do well to read Father Cekada’s poignant theological analysis of the properly translated prayers of the Novus Ordo Missae before “shouting from the rooftops” with joy that a de-Catholicized liturgy that has more in common with a Lutheran or Episcopalian worship service is finally, 40 years after its creation, going to have a more accurate translation in English. In other words, the translation of the Novus Ordo Missae, which Archbishop Annibale Bugnini and his cohorts began deconstructing in 1948, is but the tip of the iceberg when compared to the destruction of the entirety of the Traditional Roman rite of Holy Mass — translation issues aside.

BRIAN MERSHON’S REVIEW: Many of you may be familiar with Father Anthony Cekada’s short booklet entitled Problems with the Prayers of the Modern Mass, originally published by TAN Books. As Catholics are about to become inundated with news stories and catechesis from the pews on the new translation of the Novus Ordo Missae in English, which goes live this Advent, every Catholic would do well to read Father Cekada’s poignant theological analysis of the properly translated prayers of the Novus Ordo Missae before “shouting from the rooftops” with joy that a de-Catholicized liturgy that has more in common with a Lutheran or Episcopalian worship service is finally, 40 years after its creation, going to have a more accurate translation in English. In other words, the translation of the Novus Ordo Missae, which Archbishop Annibale Bugnini and his cohorts began deconstructing in 1948, is but the tip of the iceberg when compared to the destruction of the entirety of the Traditional Roman rite of Holy Mass — translation issues aside.

From the initial changes of the rite of Holy Week in the mid-1950s, approved by Pope Pius XII, to the ongoing destruction of the traditional Roman rite, which modern version now has 13 Eucharistic prayers and only 17 percent of the orations (prayers) of the Traditional Roman rite remaining in their original substantive form, Father Cekada systematically traces the history of the destruction and minutely documents, using the very words of the reformers themselves, and shows the reader the theological de-Catholicizing caused by the final product — even when translated more faithfully beginning in Advent 2011. The Latin product, regardless of translations, is de-catholicized. It may be valid in many cases — or even most — but it lacks the fullness of Catholic theology found in the Traditional Roman rite.

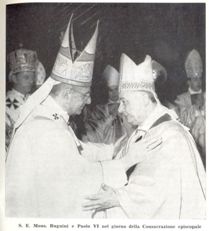

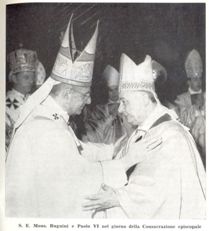

Paul VI and Bugnini

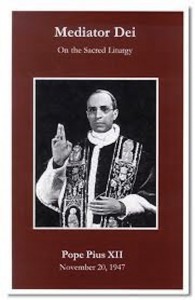

In the book’s Appendix, and indeed throughout the course of Father Cekada’s detailed work, he raises an issue that most traditional Catholics rarely consider. Because the Bugnini-led reformers, albeit with the approval of Pope Pius XII, began their systematic and well-thought-out process for destruction of the Traditional Roman rite long before the advent of the Second Vatican Council, why do traditionalist Catholic priests and laity settle for the 1962 version of the Roman rite? He analyzes the case for the 1951, 1958 and 1962 missals and makes a strong case for the use of the 1951 missal from a theological and historical perspective. While some of the traditional Societies of Apostolic Life along with a few other individual priests continue to celebrate the pre-1958 Holy Week, Father Cekada presents a strong theological case for the use of the 1951 version — prior to the Bugnini interventions that were merely designed as stepping stones for the ultimate 1970 new rite of Mass.

While the liturgical and theological scholar reader will be pleased to find Father Cekada’s copious footnotes for further reading and analysis, Work of Human Hands is not simply a dry, theological tome, but is indeed a witty, readable work easily digestible by most well-read Catholics and others who have interest in the deeper reasonings behind the replacement of the Traditional Roman rite, with as Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger once opined, “a banal, manufactured, on-the-spot product.”

Work of Human Hands exhaustively details how the reformers claimed to reinstitute many prayers and rituals used in the early Church that had supposedly become corrupt through the passage of time. Even if this misguided hankering to return to the pristine early Church’s liturgical worship style was legitimate and not already condemned by Pope Pius XII in Mediator Dei (he called it “antiquarianism”), the facts prove otherwise. The author shows how the historical evidence for many of the changes to pre-Tridentine times was merely a ruse developed by the modernist reformers in order to implement their ecumenical, assembly theology, “priesthood of all believers” agenda.

“Who, after all, ever heard a liturgist advocate restoring such primitive Christian practices as requiring women to wear veils at Mass, separating the sexes in church on opposite sides of a curtain, imposing public penances for sins of adultery or announcing heretics, Jews and pagans had to leave?” Father Cekada rhetorically questions.

“Who, after all, ever heard a liturgist advocate restoring such primitive Christian practices as requiring women to wear veils at Mass, separating the sexes in church on opposite sides of a curtain, imposing public penances for sins of adultery or announcing heretics, Jews and pagans had to leave?” Father Cekada rhetorically questions.

Most incredible perhaps is the author’s ability to show how Catholic theology, prominent throughout the Traditional Roman missal, whether the 1951, 1958 or 1962 variety, was excised and replaced in the missal of Pope Paul VI. Reparation for sins, sacrifice of propitiation, the need for universal penance, fasting and almsgiving, fear of hell and damnation finds little, if any place in the new Missal. The so-called “negative theology” that does not fit the needs and mentality of modern man has been excised. The instances in which these distinctly Catholic doctrines were suppressed, or at best, severely watered down in the texts of the new missal are staggering — even to the most diehard traditional Catholic.

Finally, I would be remiss if I ignored Father Cekada’s assertion of his belief (albeit backed up with post-Conciliar sacramental theological references) that the Novus Ordo Missae is invalid. Father Cekada is also known for his views that the reigning Pontiff, Pope Benedict XVI, and his predecessors back until Pius XII, are/were not valid Popes. I do not personally share those views, but they are not prominent within this work. The fact that a sedevacantist priest has written an exhaustive, detailed analysis of the rupture between the Mass of Pope Paul VI and the 1962 Missal and prior, does not mean the contents of his analysis are untrue. In fact, again, using the words of the prominent liturgical reformers and Pope Paul VI, Father Cekada proves their intentions, and even further, shows that Pope Paul VI was actively involved and a primary proponent of the new theology in the resulting Missal bearing his name.

I highly recommend this book — even reading it multiple times as I myself did — to interested Catholic laymen, but especially to priests, who desire to understand in excruciating detail the theological reasons behind the rupture with liturgical and theological tradition caused by the use of this new rite of Mass for the past 40 years. Father Cekada’s exhaustive theological critique demands a response from the “reform of the reform” crowd. I doubt one will ever be forthcoming however. New translations will not make the Novus Ordo Missae more theologically Catholic. A pig with lipstick is still just a pig.

(Originally published online on January 14, 2012 at www.renewamerica.com)