Rev. Dr. Alcuin Reid

• “Carefully argued.

• “Well researched.”

• Ably demonstrates that “The Mass of Paul VI remains, in its Latin original… intentionally theologically different to what came before.”

• “The book as a whole succeeds in demonstrating the substantial theological difference between the two missals.”

• “Also succeeds in demonstrating the impact of a doctrinally different rite on the belief of the faithful.

• “Father Cekada’s great service is to flag the big question that we have not widely, as yet, been prepared to face…

• “If the Missal of Paul VI is indeed in substantial discontinuity with the preceding liturgical and theological tradition, this is a serious flaw requiring correction.”

• “It is high time, then, that we not only recognize, but do something about the elephant in the liturgical living-room.”

REVIEWER: The Rev. Dr. Alcuin Reid is a liturgical scholar and cleric of the Diocese of Fréjus-Toulon, France.

Dr. Reid with Cardinal Ratzinger

Dr. Reid is not well known in old-line traditionalist circles (independents, SSPX, sedevacantists, The Remnant, etc.), but is very well known among the younger and more conservative generation of post-Vatican II clergy who in the mid-1990s started to question the official liturgical reforms. He has written numerous articles and lectured at international conferences promoting the application of Benedict XVI’s Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, which gave a general permission for celebrating the Mass according to the Missal of John XXIII.

Dr. Reid’s academic reputation was secured by his monumental work, The Organic Development of the Liturgy: The Principles of Liturgical Reform and Their Relation to the Twentieth-Century Liturgical Movement Prior to the Second Vatican Council (Ignatius Press 2005). This is a survey of the history of liturgical change and development up to the eve of Vatican II. The second edition in 2005 contained a laudatory preface by Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger. Dr. Reid is currently at work on a successor volume entitled Continuity or Rupture? A Study of The Liturgical Reform of the Second Vatican Council, which is due to be released in 2013.

I should add here that I am greatly indebted to Dr. Reid for the many insights that Organic Development provided me with as I was researching Work of Human Hands. His work was particularly helpful as I was trying to sort out and understand the theories of the German Jesuit liturgical scholar Josef Jungmann that would greatly influence the creation of the Novus Ordo

WEBSITE: New Liturgical Movement (NLM) is a website founded in 2005 by Sean Tribe, and dedicated to “the Sacred Liturgy and liturgical arts.” It has an international list of contributors and promotes the celebration of liturgical ceremonies according to both the pre- and post-Vatican II rites.

WEBSITE: New Liturgical Movement (NLM) is a website founded in 2005 by Sean Tribe, and dedicated to “the Sacred Liturgy and liturgical arts.” It has an international list of contributors and promotes the celebration of liturgical ceremonies according to both the pre- and post-Vatican II rites.

NLM regularly posts photos of ceremonies conducted in the traditional rite under the auspices of diocesan bishops or Vatican-approved priestly societies (Fraternity of St. Peter, Institute of Christ the King), and, in the case of the Mass of Paul VI, encourages the use of more traditional externals, such as Latin, chant, polyphony, ornate vestments, and reciting the Eucharistic Prayer “facing East.”

THE REVIEW. I was very pleased to have Work of Human Hands reviewed by Dr. Alcuin Reid. His review of Work of Human Hands is well-crafted and systematic, and he examines the material in the order in which I presented it. The full text of is available on NLM at this link.

Dr. Reid's "Organic Development"

I. Positive Observations. Dr. Reid begins with kind words for my 1991 study on the orations, Problems with the Prayers of the Modern Mass, which he says alerted him to “the significant theological difference between the pre-conciliar and the post-conciliar Roman Missals.”

Work of Human Hands, Dr. Reid says, “is a substantial attempt to demonstrate profound theological rupture between the two,” adding that “it deserves serious attention.”

Like other reviewers, he correctly notes that I am a sedevacantist, but warns that this fact is “not sufficient to dismiss this carefully argued and well researched work. We must attend to his arguments on their merits.”

Dr. Reid then recapitulates the principal thesis of Work of Human Hands, that it, the overall conclusion I propose to draw from the evidence I present:

The principal thesis is that “the Mass of Paul VI destroys Catholic doctrine in the minds of the faithful and in particular, Catholic doctrine concerning the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the priesthood and the real presence,” and that it “permits or prescribes grave irreverence.” … His practical conclusion is that “a Catholic may not merely prefer the old rite to the new; he must also reject the new rite in its entirety. The faith obliges him to do so.”

Given that the many of the readers of his review still regularly assist at the Novus Ordo, Dr. Reid adds:

These strong, even extreme, positions may themselves repel readers. But again, they must be examined.

In the next few paragraphs, Dr. Reid criticizes my approach to some of the historical background to the New Mass that I provided in Chapters 2 and 3, which dealt with, respectively, the Liturgical Movement and the creation of the New Mass. (See below.)

He then says:

However, the meat of Cekada’s work is found not in his history, but in his theological analysis of the Mass of Paul VI.

General Instruction on the Roman Missal

Two chapters are devoted to an analysis of the different versions of the General Instruction of the Missal that appeared in 1969 and 1970. Cekada rightly points out that the 1969 text confidently outlined the prevailing theological principles that underpinned the reformed rite of Mass, which was published with it.

Cekada demonstrates well (but with a bit too much rhetoric) that these principles leave traditional Catholic theology behind: “sacrifice” is replaced with “assembly”, “the Lord’s supper” moves in to displace “the Sacrifice of the Cross”, etc.

This provoked a controversy over the New Mass when it first appeared in 1969, and the famous Ottaviani Intervention, which declared that the Novus Ordo “represents, both as a whole and in its details, a striking departure from the Catholic theology of the Mass as it was formulated [at] the Council of Trent.”

Note that Cardinal Ottaviani speaks about the rites, not the Instruction. As Cekada ably demonstrates, the theological principles so boldly outlined in the 1969 Instruction guided the decisions about what went, remained, or was invented for the rites of the Mass of Paul VI (just look the Offertory).

The dispute over the Instruction led to the issuance of a revised version in which, as one liturgical progressive of the period noted, a more “Tridentine” term was placed alongside each incriminated expression.

However, as Cekada deftly observes, the prayers and rites of the 1969 Order of Mass are identical to those of 1970: a defective building is not rectified by scribbling a few changes on the blueprints.

The Mass of Paul VI remains, in its Latin original (before any Episcopal Conference gets to mistranslate it), intentionally theologically different to what came before.

I was particularly pleased that Dr. Reid gave so much attention to the two chapters on the General Instruction (Chapters 5 and 6), because the issues they address are crucial in understanding the theological disconnect between old and new.

Over half of this book is given over to a detailed exposition of this difference, not at all unsuccessfully. Cekada draws frequently on the writings of those responsible for the reform itself, who state the difference plainly. (One of the strengths of this work is its research and detailed footnotes and bibliography).

To take but one example, Cekada’s exposition of the theological reform of the orations―the collect and other prayers (pp 223-228) ― brilliantly demonstrates that, as Father Carlo Braga boasted at the time, the “doctrinal reality” of the texts was altered in the “light of the new view of human values” and “ecumenical requirements”, as well as “an entirely new foundation of Eucharistic theology.”

To take but one example, Cekada’s exposition of the theological reform of the orations―the collect and other prayers (pp 223-228) ― brilliantly demonstrates that, as Father Carlo Braga boasted at the time, the “doctrinal reality” of the texts was altered in the “light of the new view of human values” and “ecumenical requirements”, as well as “an entirely new foundation of Eucharistic theology.”

My only regret here is that this is not augmented with references to the excellent and detailed work being done on the same topic by Professor Lauren Pristas.

Nevertheless, here, Cekada makes his point very well. Indeed, it has to be said that the book as a whole succeeds in demonstrating the substantial theological difference between the two missals.

As regards the effects of these changes:

[Cekada] also succeeds in demonstrating the impact of a doctrinally different rite on the belief of the faithful. Surveys on the decline in belief in the real presence amongst Catholics are sufficient to underline that.

II. Criticisms and Disputed Points. The major ones concern my position on the invalidity of the New Mass, the historical material I present in Chapters 2 and 3, and the connection between the Liturgical Movement and modernis.

1. The Invalidity of the New Mass. Here, Dr. Reid is incorrect in his review when he states that the “secondary thesis” of Work of Human Hands is that the Mass of Paul VI is invalid.

I do indeed argue that the new rite is invalid — due to substantial changes in the form of the sacrament that alter the intrinsic sense of the words, and so change the ministerial intention — but I devote a scant three pages (346–8) to the issue.

I do indeed argue that the new rite is invalid — due to substantial changes in the form of the sacrament that alter the intrinsic sense of the words, and so change the ministerial intention — but I devote a scant three pages (346–8) to the issue.

It was necessary to treat this issue in Work of Human Hands not only because it is a question that traditionalists inevitably raise, but also to indicate the consequences of the theology embodied in 1969 General Instruction. The new “assembly theology” rejected scholasticism, the notion of a sacramental form, and Words of Consecration, substituting “narrative” and “words of the Lord.”

Implementing that theology in the new rite was bound to have effects, and it was the Ottaviani Intervention itself that first raised the specter of invalidity as arising from changes in the form. (See pp. 44, 60, note 29)

2. Historical Questions. Dr. Reid has dedicated several decades to researching and analyzing the historical background to the Vatican II liturgical reforms, so his criticisms on historical questions in particular must taken seriously.

Dr. Reid believes that I attribute too much to Bugnini in my treatment of the pre-Vatican II liturgical changes.

Father Annibale Bugnini is pivotal, of course. But the idea that prevails here, and elsewhere, that he held the reins of power in all liturgical reform from 1948 onward, carefully manipulating and conspiring towards the goal of the new Mass, is false. Bugnini was an activist and an opportunist, certainly. However, as Msgr Giampietro’s study of Cardinal Antonelli’s liturgical role, The Development of the Liturgical Reform, demonstrates, Bugnini was by no means the principal or sole architect of the liturgical reforms of Pius XII.

Mgr. Annibale Bugnini

I willingly concede that Bugnini was not the only player. The difficulty is that, compared with others involved in the reforms, Bugnini was a relentless self-promoter who wrote extensively about his own work whenever possible. It is perhaps inevitable that such a character would sometimes get more credit (or in the case of the reform, more blame) that he deserved.

But as regards what followed Vatican II, says Dr. Reid, Bugnini’s moment came later, in 1963:

when his friend, Cardinal Montini, became Paul VI and rehabilitated him, naming him secretary of the commission to implement the Council’s liturgical reform. This singular opportunity and their frequent personal collaboration is what brought about the Mass of Paul VI.

I anticipate that the successor volume to Dr. Reid’s Organic Development will provide many more interesting details about this collaboration that were previously known,

On the same question of my treatment of the 1950s reforms, Dr. Reid makes the somewhat surprising comment:

It must be said that [Cekada’s] veneration of Pius XII, and his exoneration of him from any responsibility for the liturgical reforms of the 1950s, is excessive. The fact is that we do not know the extent of Pius XII’s personal enthusiasm or involvement in their realisation. But we do know that they were enacted on his authority. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, for better or worse, the responsibility for them is his.

I had rather expected that my treatment of Pius XII might be regarded as too harsh!

Moving to the section of Work of Human Hands that deals with Vatican II and the period immediately following, Dr. Reid says

Cekada’s history of the Vatican II reform is better, though to treat the discussion of liturgical reform at the Council itself in but three paragraphs, and the intense activity of the following five years in but ten pages is rather thin; and there are occasional inaccuracies.

In response I would say that the chapter to which Dr. Reid refers was merely intended to provide an overview of what went on. I anticipate that the second volume of his Organic Development, scheduled to appear in 2013, will treat this period in far greater detail than I could ever hope to.

3. The Liturgical Movement and Modernism. Dr. Reid’s strongest criticism of Work of Human Hands concerns my treatment of the 20th century Liturgical Movement and what I maintain is its intimate connection with theological modernism. Here Dr. Reid says:

Unfortunately this history is not dispassionate. It makes the mistake of repeating the all-too-frequent shrill cries of “modernism” that abound in Father Didier Bonneterre’s slim work, The Liturgical Movement, which I have reviewed elsewhere as “not a study that reaches a conclusion, but a conclusion which seeks the support of a study.”

Abp. Conrad Groeber

Here, though, it was not just post-Vatican II traditionalists who raised this issue, but actual contemporaries of the Movement: Archbishop Groeber and several others in the 1940s (see pp. 18-9) and Ernest Koenker and others in the 1950s (see pp. 44-5). In the latter case, Koenker praised the leaders of the Movement for having adopted the very methods condemned by Pius X in Pascendi.

As regards some particular personalities in the Movement, Dr. Reid says:

That is not to say that those at whom the finger is pointed ought not to be scrutinized. Dom Lambert Beauduin certainly inaugurated the pastoral liturgical movement, but anyone who studies his seminal work Liturgy the Life of the Church can see that this was both sound and traditional. Beauduin’s ideas developed, yes, and he became a suspect ecumenist, certainly, but there is no evidence that he conspired towards or would have been happy with the missal of Paul VI.

The influence of the Jesuit scholar Joseph Jungmann ― expounded very well here ― is certainly crucial.

Louis Bouyer’s liturgical theology was definitely different to the prevailing twentieth century scholasticism, but that does not mean that it is necessarily modernist or heretical: theological development is possible so long as it does not deny truths of the faith.

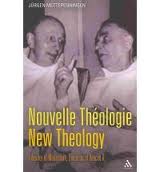

"Heirs of modernism, precursors of Vatican II"

But again, one salient characteristic of modernists is their rejection of scholastic theology (one point on which Koenker praised the Movement). And here the Liturgical Movement counted among its supporters many adherents of the anti-scholastic nouvelle théologie (the new theology), which was condemned under Pius XII and triumphed at Vatican II. Contemporary theologians now regard the leading lights of the nouvelle théologie as having been the successors of the modernists whom St. Pius X had condemned and as the precursors of the theology of Vatican II.

The connection, moreover, between the theology of the Mass that Bouyer enunciated in Liturgical Piety and the assembly theology of the 1969 General Instruction which Dr. Reid rightly regards as pernicious would seem to raise serious problems about defending Bouyer’s orthodoxy.

I will concede, however, that much more research needs to be done regarding the influence of modernism upon the Liturgical Movement, as well as the necessary connection between traditional Catholic theology and the traditional liturgy

The conclusion that I believe will ultimately emerge is this: Without scholastic theology behind it, the traditional liturgy in the modern age, no matter how splendidly executed, becomes nothing more that a gorgeous shell emptied of its substance. And that in turn, I hope, will lead to a rejection of the new theology in favor of the old.

III. Conclusion. Dr. Reid concludes his review with a rather ringing recommendation, accompanied by a call to action:

Regardless, Father Cekada’s great service is to flag the big question that we have not widely, as yet, been prepared to face. Whilst it is certainly better to celebrate the modern liturgy in a traditional style using more accurate translations, that is not enough.

For if the Missal of Paul VI is indeed in substantial discontinuity with the preceding liturgical and theological tradition, this is a serious flaw requiring correction.

It is high time, then, that we not only recognize, but do something about the elephant in the liturgical living-room.

In sum, I was particularly pleased that throughout his review, Dr. Reid sought to emphasize my discussion of the underlying theological problems with the Mass of Paul VI. It was precisely this aspect of the New Mass that I wanted to draw attention to.

For this reason, I tried to make Work of Human Hands a sort of synthesis or summary of how the texts, gestures and rubrics of the Mass of Paul VI undermined belief in Catholic doctrine on the nature of the Mass, the priesthood, the Real Presence, etc.

We all know that the process took place, and that the reformed liturgy played the key role in it. The tendency (it certainly was mine many years ago) was to blame “abuses” — deviations from the officially prescribed norms. But as the years have rolled on, it has become more and more apparent that the officially-sanctioned rites themselves (even in Latin) are true source of the problem.

I am grateful to Dr. Reid for his thoughtful review, and I am grateful to New Liturgical Movement for publishing it.

May it impel more Catholics, as Dr. Reid says, to “do something about the elephant in the liturgical living-room.”